There are a few types of aerospace propulsion that I think most of us have heard of: propellers, or props, which most smaller planes use, jet engines, which virtually every other plane uses, and rocket engines, which, well, rockets use. While these are the most common options out there, there exists a whole world of actual and theoretical propulsion methods that could be just around the corner. So around the corner, in fact, that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the United States Airforce just gave millions of dollars to the aerospace start-up Wave. [1] Wave Engine Corporation earned this money with their field-tested wave (or “pulsejet”) engine technology. Today we’ll explore what this even is, how it works, and why it could rock the aviation and aerospace industries.

Very simply, jet engines and props use gas to spin rotors that push air backward (like a fan pushes air forwards). One of Newton’s silly laws states that: for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. When the air is pushed backward, the plane is pushed forward. That’s thrust in a nutshell. The more air you can push backward and the faster you do it, the more thrust you have.

Rockets work a bit differently—they can’t push the air around them backward, because there’s no air in space, so when they burn fuel, they accelerate that gas and shoot it out the back. The result, however, is similar—the more gas they can push out faster, the more thrust the rocket generates. Because rockets push their actual fuel backward, they have to use a lot more of it than planes. In other words, rockets are much less efficient. So they’re great for a three-minute flight up to space, but not for an eight-hour trip from New York to Italy.

So where does the fancy new Wave Engine fall in this spectrum? The short answer is just to the right of Jet Engines. But let’s figure out why.

These engines work essentially the same way rockets do—by mixing fuel and oxygen, blowing it up, and shooting it out the back. There are two main reasons, however, that these engines are able to burn less fuel than rockets (i.e. moving from right to left on the chart). The first is rather obvious, this gas isn’t continuously being shot out the back, it’s done in pulses—hence “pulsejet”. Therefore, it uses less fuel. It’s able to do this because the wings of the plane keep it level and flying when the engine isn’t firing. Rockets don’t have this luxury. The second reason they’re better than rockets is that they’re much lighter. In space there’s no oxygen, so you have to bring it with you to set your fuel on fire. Wave engines operate in the atmosphere and thus can take advantage of the oxygen around them. This means, for the same capability, they’re almost half as heavy.

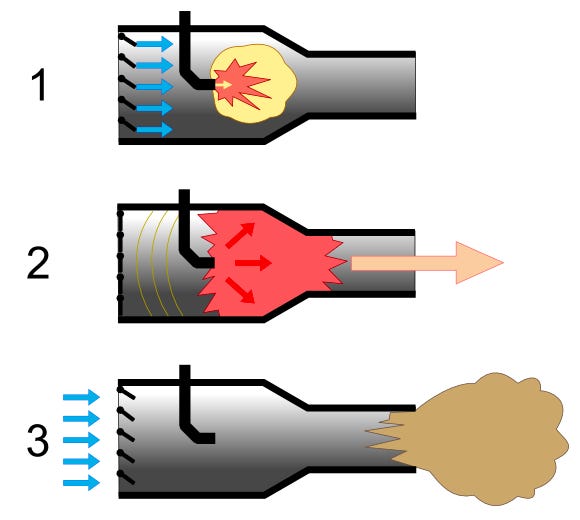

But even though they’re more fuel-efficient than rockets, they still can’t match jet engines. Here’s a fun little diagram of what a “pulse” would look like. [3]

So why, then, if they aren’t as fuel-efficient as jet engines, are they so exciting? The answer, according to Wave, lies in reliability and maneuverability. This engine requires almost no moving parts, which makes it five times cheaper to make. [1] Additionally, because it doesn’t need to suck in forward air, like jet engines, it is immune to any sort of debris flying into it. This is very unlike jet engines, which can experience things like bird strikes. While they’re not super common, they’re always a risk. With this engine, we can eliminate that.

Furthermore, these short little pulses allow for very easy thrust vectoring, which is a fancy phrase for controlling what direction the force comes out of the engine—instead of just backward. This opens up the door for rather simple Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) as well as many different otherwise complex maneuvers.

Wave won’t have commercial aircraft contracts any time soon, but they stand as one of the few propulsion companies working on this technology. The applications of this concept reach much further than you and I, or even a fighter pilot, would see. There are concepts for nuclear wave pulse engines that could be the key to hypersonic (>Mach 5) flight. It potentially puts 4,000+ mph flight within reach. Sadly, though, there wasn’t much of this information publicly available…

Thanks for reading this week’s edition of It’s Not Rocket Science. As always, I hope you learned something new, and I’ll see you next time!

Check out last week’s newsletter here.

For more details…

Cover Image: The Drive

[1] https://www.aero-mag.com/north-american-wave-engine-corporation-23062021/

Very Interesting !