Satellites Part IV: Where do they go when they die?

What do space, the Pacific Ocean, and hand grenades all have in common?

Thus far we’ve covered how satellites are actually used, how they get to space, and the types of things they do while they’re up there. Fast forward. It’s 15 years later, our satellite has almost run out of fuel, and, like Texas in a snowstorm, it’s out of power. Where does it go now? Does it just stay there? Space is pretty big; we could probably just leave it up there. After all, we don’t want it crashing back to Earth. Good intuition; and you’re not far off. Welcome to our final segment on satellites—thank you for coming along for the ride, but now it’s time to abruptly stop, and stay in space forever.

There are two main places that satellites go when they die: up or down. Let’s go down. Satellites generally don’t have heat shields—that is, they aren’t meant to withstand high temperatures. They’re mostly built for the cold. Because of this, it stands to reason that they would not fair well falling back into the atmosphere. Anyone who’s seen the space shuttle or other spacecraft re-enter Earth’s atmosphere knows that it gets hot. They’re slowing down from 15,000 mph to 400 mph in a matter of minutes. Temperatures during Earth re-entry can be up to 3,000 degrees. If a satellite is small, with very little protection, this is the path it will take. Engineers design the fuel tank to have just enough reserves to end its mission. In this case, the satellite begins to fire its thrusters forward, reducing its orbital speed. As it slows down its orbit begins to shrink. Think of a ring around Earth, slowly getting closer and closer. Until finally, the satellite is close enough to Earth to be significantly caught in its atmosphere. At this point, the satellite is entirely out of fuel and is slowing due to drag. From here the heating does the rest. Not long after the satellite began to slow down, it’s being incinerated by the heat load imposed on it. After a few minutes, there’s nothing left of the satellite but dust. That high up in the atmosphere this dust isn’t very harmful to us. It spreads out and effectively disappears.

This method is great for small things that break up easily. This is really the only way to justify directing debris going Mach 15 back towards us. Otherwise, if the satellite is bigger, there is no guarantee that it will all burn up, and there’s a high chance some pieces will come speeding down. They won’t hit the surface going as fast as they were in space. This is thanks to air resistance and a little thing called terminal velocity. Don’t worry—I wrote about that too. Anyways. What do we do with the big bois? Enter the tombstones and cemeteries.

If we can’t incinerate them, we’ll have to put them somewhere else. The first place is in the ocean. There’s an area in the Pacific that’s commonly referred to as the “Spacecraft Cemetery”. [1]

Scientists tried to pick a point as far away from any humans as possible. This way, when we have to send space trash back to Earth, it’s at least safe. I know what you’re thinking (or not thinking, I don’t know your stance): “This isn’t helping, we’re just polluting more and more of our planet. What gives?” I know, I’m pretty frustrated too, but when compared to non-space-related trash, it’s just a drop in the ocean-sized bucket. Plus, if you think that’s bad, just wait until you hear what we do with them in space! *sad face*

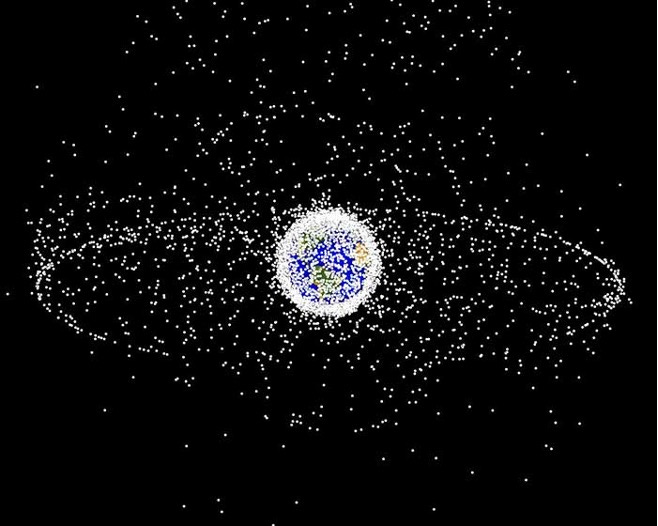

The next best place to send large, high orbit, satellites is to something called a “Graveyard Orbit”. This is an orbit like the one it’s currently in, but about 22,000 miles higher. The satellite uses its last bit of fuel to propel itself all the way out here: [1]

The dots farthest out are satellites in a graveyard orbit. Still relatively close to Earth, but far enough away from any operational satellite that there’s no chance that it could collide with anything that still needs to work. And this is where they’ll stay. Forever. In the early days of space exploration, we weren’t all too concerned about leaving things where they were. After all, we were astonished by how few things were in space as is. We could just leave satellites in their respective orbits and really not have to worry about it. They’re 15x15 foot boxes spread out over an area of 220 million square miles (141 billion acres). But over time, we’ve sent up thousands of satellites. Moreover, if any of these satellites do get hit with something, that spreads much smaller debris, which, by the way, is now traveling at orbital velocity. So not only do we have to look out for other satellites when launching, we need to look out for all the little, tiny pieces of debris that are the results of previous collisions. The current estimate is that there are more than 34,000 pieces of debris greater than 10 cm, 900,000 pieces between 1 and 10 cm, and over 128 MILLION pieces of debris less than 1 cm wide. The latter we are largely unable to track. [2] This makes space flight even more of a gamble. The good news is most of this debris is traveling around the Earth in largely the same direction. This means your satellite’s speed relative to the debris it could hit is smaller, meaning less potential damage. Even so, if you hit a stationary rock, 1 cm (0.4 inches) in diameter, traveling 15,000 miles per hour it would hit you with roughly the same amount of energy as a hand grenade. It’s safe to say that wouldn’t bode well for your fancy science equipment. This assumes a spherical rock with a density of 3 g/cm^3, if you were wondering.

This brief analysis leads us to a bad conclusion: there’s too much crap in space. Because of this, the European Space Agency (ESA) has begun a project to tow non-operational satellites back to Earth. [3] In the meantime, however, experts are genuinely concerned by this space debris, saying that eventually, we could get to a point where we’ve locked ourselves on the planet, as it would be too dangerous to fly up into orbit and beyond. This concept was proposed in 1978 by Donald Kessler and is aptly deemed the “Kessler Syndrome”. No, that’s not the same as spending an entire day entranced by an unrelated Ben Kessler’s new EP, but I like where your head’s at.

In summary, satellites go one of three places when they die: the atmosphere, the ocean, or somewhere else in space. All options present risks, but they all were originally designed to eliminate the greatest one of all: us getting stuck on Earth. Scary theories aside, they did a whole bunch during their 15-30 year lives: they were built all nice and cleanly in a lab, strapped to a massive stick of dynamite, and sent farther up in the sky than you or I could dream of. All the while they were sending us useful information, allowing us to talk to our loved ones, and letting us watch our favorite TV shows. They even let us play around with eerily high-resolution Google Maps. They surely deserve a big thank you from us when they go out in their blaze of glory.

This marks the end of our series on satellites. I hope you learned something from these, I know I did. Look out next week for some new topics laced with the same sarcastic tone. Thanks for reading!

Check out last week’s newsletter here.

Special thanks to Joe Lovinger for edits.

For more details…

I would have never known or cared about any of this without your writing — a huge thank you for expanding my awareness in such an entertaining way.